Midnight Movie / My Brilliant Friend / & Juliet / The Entertainer / seven methods of killing kylie jenner / the end of history / The Deep Blue Sea / Nigel Slater’s Toast / Closer / Goats / Manwatching / CTRL+ALT+DEL / Waiting for Godot / Educating Rita / The Hound of the Baskervilles / The Musicians of Silence / Under Milk Wood / The Birds / Henry V / Dracula / Oklahoma! / The Door / Hurricane / An Evening with Gary Lineker / West Side Story

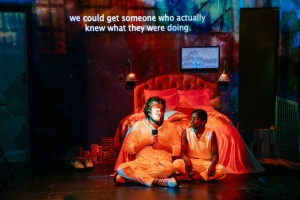

Midnight Movie ★★★★

Performed on 3 December 2019 at Jerwood Theatre Upstairs, Royal Court Theatre, London

Read the original review here

Midnight Movie manages a mean feat of being both a complex play and a simple one at the same time, which could possibly work as a metaphor for the writer’s personal battles with her illness, which are never quite truly revealed but are omnipresent all the same.

On the surface of it, the play is essentially an exploration of a modern obsession with the digital world and the ability to watch almost any video at the tap of a screen in the middle of the night. Two performers, one while male and one deaf woman of colour, act as avatars describing a series of found videos unseen by the audience, interspersed with an occasional online chat interaction. Stories of a woman on CCTV battling with an unseen terror, a man bathing in a hotel, two women killing a North Korean dictator thinking they’re on a prank TV show… It is in these moments that Eve Leigh proves to be a masterful storyteller.

Admittedly, for a while at the start I was trying to get my head around what exactly was going (the performers, at first, seemed to be stuck in an experimental play that wouldn’t look out of place in a drama school) but as the play progressed we were sucked in deeper, much like Leigh’s YouTube/internet late night rabbit hole. As we dug deeper into the play it became ever clearer how much Leigh uses the digital world to escape the confines of her painful body – to say more than this feels like a betrayal of a play that needs to be felt and experienced rather than read about.

Nadia Nadarajah and Tom Penn worked well together, Penn speaking the words aloud as Nadarajah signed and mimed much of what was being said. The set design at times worked as a third character with projections filling all three walls and nearly every single word captioned for D/deaf audience members. The only minor downside of this were it making the handful of times Penn made a slight deviation from the script more glaringly obvious. Thankfully, the cast’s performances were captivating enough for this not to be a distraction for long.

While it would have been easy to provide captioning in a rudimentary format, the text brilliantly became an integral to the play through its delivery and location around the set. Massive congratulations to designer Cécile Trémolières and lighting and video designers Joshua Pharo and Sarah Readman for this exciting and effective concept. The sound design from Nwando Ebizie also deserves a notable mention, a brilliant soundscape overall cleverly using a recurring motif of Janelle Monáe’s Make Me Feel, as well as Penn’s live drum playing.

Director Rachel Bagshaw has created a striking and interesting production from Leigh’s text which without a doubt has come from a deeply personal place but delivered in an intriguing and experimental way.

My Brilliant Friend ★★

Performed on 26 November 2019 at National Theatre, London

Read the original review here

The National presents a revived production of My Brilliant Friend on its largest stage, the Olivier, following a sold-out run at the Rose Theatre Kingston in early 2017. Adapted from Elena Ferrante’s Neapolitan Novels, writer April De Angelis has crammed the contents of four books into two plays, each lasting nearly three hours, resulting in a pair of plays that feel rushed and lacking emotion.

The story centres on best friends Lenù and Lila, played by Niamh Cusack and Catherine McCormack respectively. Part One charts their lives from children growing up in Naples through adolescence to young adulthood, the two girls almost always by one another’s side. Act one introduces a whole community of characters, some evidently more important than others as the play progresses, begging the question of what their purpose is other than to create a bustling backdrop and uneasy threat of background violence.

The answer sadly doesn’t appear in Part Two. The earlier threat of the Solara family grows ever stronger, the plot moves to Florence and the tale details how the women have forged their own separate paths, but many of the earlier characters are either forgotten or seemingly unnecessarily reintroduced.

This isn’t to suggest the performances throughout aren’t strong – far from it, the entire company are excellent throughout. McCormack, in particular, delivers a consistent sense of unease and unpredictability. As Part One progresses, Cusack’s Lenù gets stronger, developing her own identity aside from Lila. In Part Two, Lila points out she was always “the bad one”, something confirmed by another character later in the play, and yet Lenù’s choices become questionable even if they are driven by a strong motive.

The set in both parts consists of the huge Olivier stage and a series of concrete steps on castors, moved around as necessary, and projections filling the space. However, this all drowns out the intimacy in many of the scenes in both parts, the actors struggling to draw an audience in whilst lost in the space. Even when the stage is at its most sparse, the characters feel too distant.

The biggest fault of the play is the tendency to rattle through as many scenes as possible, many of which only last a few minutes to touch on a plot point before rushing on to the next. Nothing is allowed to settle, there isn’t time for emotion to be felt or breathed, or for the audience to think about what has been witnessed, and this very much works against the play. For example, there are two memorable sexual assaults in Part One but rather than reflecting on their impact we’re whisked on to the next plot point, and the next, and the next. The use of popular music in the numerous scene changes, while useful in setting the scene of which era the action takes place, also punctuates in a jarring way.

There are many clever stylistic moments peppered throughout the play, in particular the use of puppetry of clothing during the aforementioned assaults being particularly striking. But this is contrasted with the use of blank puppets as our protagonists’ young children becoming a distraction rather than an integration into the play. Melly Still’s direction should be commended for the strong visual eye but the whiplash pace of the production and regular moving of the staircases reduced the opportunity for the audience to connect with the characters.

A good adaptation would ordinarily take key characters and plot points, build upon them and breathe new life into a story for a different audience. I can’t claim to have read Ferrante’s books and I’m sure De Angelis left out a lot of content, but unfortunately My Brilliant Friend feels bloated and unnecessarily long.

& Juliet ★★★★★

Performed on 20 November 2019 at Shaftesbury Theatre, London

Read the original review here

Max Martin may not be a household name but without a doubt you’ll know loads of the pop songs he’s co-written over the past twenty plus years – the likes of …Baby One More Time, I Kissed a Girl, Since You Been Gone – and it’s this huge back catalogue that forms the basis of the brilliant & Juliet.

We start at the premiere of superstar writer Will Shakespeare’s latest blockbuster Romeo & Juliet, his wife Anne Hathaway having gotten a babysitter and travelled to London to see it. It is her question of “what if Juliet didn’t kill herself at the end?” that kickstarts a whole new story, written by both Anne and Will, and the premise for the musical. Will doesn’t give in easily and the two battle it out to the lyrics of a Backstreet Boys classic.

Act One focuses on Juliet and her friends travelling 600 miles to start afresh in Paris. We’re introduced to non-binary May battling with issues of gender identity, Juliet’s nurse is fleshed out and given a name (Angelique), and Anne creates the character April so that she can be part of the play too. Upon arrival they attend a ball and a love triangle is formed when Francois du Bois meets both Juliet and May on the same night.

What unravels over two acts is an evening of pure joy, a tale of female empowerment and self love, with in-jokes for the Shakespeare nerds and hilarious shoehorning of songs into the plot. But where this might be a criticism in other musicals, in & Juliet this is just part of the mischief and merriment of the production – as a fan of the songs you can’t help but enjoy how they’ve been made to work. Some songs fit quite naturally into the plot, sometimes hard to imagine they weren’t written especially for the show, whereas with others tongues are very firmly in cheeks. But that just makes it all the more fun.

There’s some brilliant mash ups (a personal favourite was Ariana Grande’s Problem colliding with Can’t Feel My Face by The Weeknd) and overall Bill Sherman’s reimagining of pop classics into musical numbers works a treat (the comic timing of the lyrics to Since You Been Gone are particularly memorable). Same goes for David West Read’s book cleverly stringing the songs together into a genuinely interesting and funny story, a comedy even Shakespeare would have been proud of.

Although this is very much Juliet’s story, the plot with the most substance to it was the exploration of Will and Anne’s marriage and the similarities to the star crossed lovers’ fateful relationship. Cassidy Janson as Anne steals the show with her witty performance and powerful voice. Similarly, Oliver Tompsett’s Will wonderfully brings us a celebrity in crisis via the strength of powergrab dance moves. Tim Mahendran too was hilarious as Francois.

The performances across the production are brilliant and I’ve no doubt this will be the start of a massive career for Miriam-Teak Lee following her starring role as the titular heroine. The set and costume from Soutra Gilmour and Paloma Young are bold, brash and explosive and work brilliantly for this contemporised historical backdrop.

But the real star of the show is the brilliant music. There’s no point in denying this is a jukebox musical (it literally starts and ends with one stage), but that’s no bad thing when the songs are this good and are made to work in this way. The second act may have felt a little rushed, with Francois’s reconciliation with his father falling victim to what could have been a hugely emotional moment, but when you find yourself smiling from beginning to end, who cares?

As the house lights came up, my first words were “I already want to see it again” and I don’t think I can give it much higher praise than that.

The Entertainer ★★★

Performed on 24 September 2019 at New Victoria Theatre, Woking

Read the original review here

John Osborne’s revered classic play The Entertainer is nearing the halfway mark of a three-month UK tour and has just arrived at the New Victoria Theatre in Woking. Director Sean O’Connor has cleverly transferred the action from the 1950s Suez Crisis backdrop to 1982 and the height of the Falklands War in what is unfortunately an uneven production.

Previously performed by Laurence Olivier and Kenneth Branagh, old-school entertainer Archie Rice is brought to life by Shane Richie in a role he was born to play. Originally written as an end of the pier entertainer struggling to compete with new cultural changes such as fashion and televisions in the home, Richie’s Archie becomes an old-school comic on the club scene struggling against the rise of political and politically correct humour.

As such, the audience are invited to question the suitability of Archie’s gags in his opening routine. The old familiar ones about overweight women and mother-in-laws are well written and arguably still funny, but it does make the audience wonder why such humour was ever mainstream. By placing a famously entertaining performer like Shane Richie in the lead role adds an uncomfortableness for the audience – does the likeable Richie allow us a pass at laughing at these jokes? Regardless of these bigger questions, Richie is joyous as the self-destructive glory-hunting Archie.

The play flits between the comedy routines and the Rice family’s home life. Archie’s elderly father Billy is immediately introduced as a casual racist espousing his patriotism and ‘back in my day’ sentimentality. Pip Donaghy is faultless in the role, even if his Alf Garnett bigot act is scarily familiar.

Diana Vickers steals the show as Archie’s daughter Jean from his first marriage. Escaping an argument with her fiancé and revealing she’d attended an anti-war march the weekend before, Jean acts as a modern day moral compass, questioning her family’s views be it through argument or subtle raise of the eyebrow. However, her accent caused some confusion – Jean has “come up” from London where she has been working and studying, yet is the only northern voice among the cockney family. This confused the location and backstory, often detracting from the plot in hand. However, this shouldn’t discount Vickers’s excellent performance.

Sara Crowe was often grating as Archie’s wife Phoebe but it’s hard to tell if this was a deliberate decision from the production. Crowe’s moments when Phoebe is drunk late at night were entirely believable, never letting an argument drop when it should have long passed. Outside of these moments though, her performance doesn’t quite ring as true.

The production has some interesting touches throughout – the recurring symbol of the Union Jack in bunting and on a jacker a reminder of the family’s blind patriotism; familiar headlines from The Sun setting us firmly in Falklands-era 80s.

Yet something feels off and it’s hard to put a finger on quite what it is. There are moments when the fourth wall is broken in mistimed interludes, and the confusion around permission to laugh with Archie in his stand-up sets puts the audience on an uneven footing. Some of Billy’s racist lines appear to be delivered directly at the audience, possibly as an attempt to shock us. It’s hard to say.

For all its faults, there’s no doubting The Entertainer in this revised form is a timely reminder of history repeating itself even today – a major crisis tearing the nation apart as people question their values, responsibilities and what they deem acceptable.

seven methods of killing kylie jenner ★★★★★

Performed on 10 July 2019 at Royal Court Theatre, London

Read the original review here

It’s 5 March 2019 and two young women drag a body through the darkness to bury it in the stage. A few hours earlier, Forbes tweeted that Kylie Jenner became the youngest self-made billionaire ever, and it’s here this important and brilliant new play by Jasmine Lee-Jones begins.

seven methods… takes places in two spaces – the Twittersphere and IRL (or, in real life for those unfamiliar with the term). In reply to the Forbes tweet Cleo, a young black woman, tweets as her online persona @Incognegro saying “YT woman born into rich American family, somehow against all odds, manages to get more rich……” along with a meme of a black woman slow clapping. Her Twitter thread continues to accuse Jenner of appropriating black culture to be lapped up by white people before suggesting killing off the “con artist-cum-provocateur.”

Danielle Vitalis is phenomenal as Cleo/Incognegro – her frustrated anger pouring out in a mix of bitingly sharp eloquent speeches and tweets. She argues Jenner is “about as self-made as my bed”, pointing out the Forbes tweet represents hundreds of years of “anti-blackness, positive affirmations of capitalism, cultural appropriation”, white people profiteering from the pain of black women. Over the course of nearly 90 minutes, Vitalis presents Cleo’s opinions with passion and superbly delivers Lee-Jones’s use of Twitter acronyms, slang and, as her friend Kara puts it, “dissertation” -speak.

But this is by no means a one-woman show. Tia Bannon is equally brilliant as Kara, Cleo’s black mixed-race queer friend, who confronts Cleo’s use of online violent language as unnecessary. Bannon possibly has more opportunity to showcase a greater range of emotions, her upset at Cleo’s historic tweets and personal attacks (comparing her being mixed raced to being like diluted Ribena) resonating strongly with the audience. At times some of Kara’s responses to things she doesn’t understand feel a little repetitive but this is a minor quibble in an otherwise brilliant text.

Despite what the title suggests, this isn’t a play that only focuses on said fantasy homicide, nor does it only concentrate on black culture as this review may suggest. It spirals and sprawls to cover long held grudges, homophobia, racialism and racial stereotypes, gender identity, memes, the ramifications of airing your views in a public domain… the list goes on. But at no point does it feel like it’s all too much – it’s not so much overflowing with ideas but rather it attends to everything with due care, respect and attention.

It’s an interesting script to look at too in a visual sense, unlike any I’ve seen before. Not only does Lee-Jones use emojis and screengrabs but there are memes and animated gifs in there too. A note at the beginning of the text encourages the actors to embody these elements and the monstrous transformation from IRL to Twittersphere really helps mark out the difference between the two spaces along with the brilliant technical aspects of the show.

Rajha Shakiry’s design is simple but stunning – a giant web made of hundreds of threads cleverly evokes the play’s Twittersphere while the occasional strands hanging down resembling the braids and weaves the young women discuss, the thicker parts reminiscent of American lynchings. The design complements the text perfectly, as does Elena Peña’s sound design – the tweeting of birds as the audience enters another intelligent nod of what is to come, and the live distortion of voices in the Twittersphere along with Delphine Gaborit’s hugely effective movement brings to life the often horrific nature of the online world.

Alongside director Milli Bhatia, Jasmine Lee-Jones has created a production that is eye-opening, provocative and devastatingly powerful in its takedown of accepted societal norms. Clever, funny, heart-breaking and brutally honest, seven methods of kylie jenner is a near perfect play and one that needs to be seen.

the end of history ★★★

Performed on 3 July 2019 at Royal Court Theatre, London

Read the original review here

Jack Thorne is very much hot property at the moment with recent hit Channel 4 dramas The Virtues, Kiri, and National Treasure each feeling like they have something vitally important to say on contemporary issues, not to mention the epically successful Harry Potter stage play among his numerous stage credits. He’s an incredibly talented writer but unfortunately I spent most of his latest play the end of history… struggling to find the point of it.

That’s not to say it’s a bad play – it’s well performed and directed, there’s some snappy lines and great performances from a strong cast. It is just… fine, and nothing more.

It’s 1997 in Newbury and leftie parents Sal and David wait to meet eldest son Carl’s new girlfriend Harriet for the first time, while their youngest Tom is being kept behind in detention for a rebellious act they’re proud of. Middle child Polly is back from Cambridge University for the occasion but spends most of the time trading barbed intellectual jibes with her father. All three children show signs of promise but, although undoubtedly loved, live in the shadow of socialist ideals from their parents.

Kate O’Flynn delivers a quirky and awkward Polly, constantly butting heads with David Morrisey as her father, and has some of the play’s best lines. Her sibling rivalry with Sam Swainsbury’s Carl is also fun to watch, as is the excruciating introduction of Harriet, played with brilliant embarrassment by Zoe Boyle. The normally excellent Lesley Sharp at times feels like she is forcing her character’s slight eccentricity, to the point we could almost see the punctuation marks on stage as she took on her scripted awkwardness. Thankfully this mellowed as the play wore on, but still felt a little out of step with the naturalism of the rest of the cast.

The play moves forward in the second act to 2007. The grown-ups have called a family meeting that has left the children concerned they’re close to losing a parent. Tom is still living at home having lost yet another job, Polly is a corporate lawyer sending nude pics to her boss, while there are obvious tensions in Carl’s marriage to Harriet, who has lost her embarrassment and is much more self-assured a decade on.

The reality of their coming together is that Sal and David want to announce the will has been altered so that any inheritance goes to various charities because, as Sal puts it, “Inherited wealth is a destabiliser, it damages those without and it doesn’t really help those with”. This proves a tipping point for Tom who does something so shocking that we could feel the family’s pain and panic all at once. Laurie Davidson is consistently devastating throughout as Tom and, along with O’Flynn, are the biggest successes of the production.

The calendar changes again and we skip forward to 2017 for the final act. The kitchen is barer now, a little less life in the house. John Tiffany’s direction is most dynamic in these act changes, a flurry of choreographed movements marking the passage of time as leaves of calendar pages are torn away, furniture is moved around and costumes are changed. But it’s not particularly interesting or new to watch – it’s a good way to show the progressing of time but there’s nothing memorable about how it was executed or anything noteworthy to pick up on.

Which sums up the play as a whole quite well. It’s an okay play with pretty standard direction on a fairly unremarkable set. I’m still unsure what Thorne was trying to say with the play – are we being warned to be careful about the ideals we place on our children? Or is it about the legacy we leave, or a reflection on the disappointment when our offspring don’t live up to expectations no matter how freethinking we claim to be?

I’m still not sure but unfortunately there isn’t enough substance to make me want to keep trying to figure it out. A good cast underserved by a funny script without much to say.

The Deep Blue Sea ★★★★

Performed on 28 June 2019 at Minerva Theatre, Chichester Festival Theatre, Chichester

Read the original review here

Terence Rattigan’s The Deep Blue Sea has recently had highly successful outings at the National Theatre in 2016 and at Chichester Festival Theatre’s main house only eight years ago, so it may come as a surprise to some for a new version to be hitting Chichester’s smaller Minerva Theatre so soon. A more intimate setting than the main house, Paul Foster’s production is an elegant and heartrending portrayal of one woman fighting the guilt of leaving her husband for an arguably less suited match.

It’s 1951 and the smell of gas alerts nosey neighbours Philip and Ann Welch to Hester Collyer’s flat. Ably assisted by their landlady Mrs Elton, the trio attempt to revive Hester while looking for clues as to what may have happened. The discovery of a note and empty bottle of aspirin suggest she may have been attempting to take her own life. As fellow neighbour and former doctor Mr Miller attends to her, Philip calls Hester’s estranged husband Sir William to inform him of his wife’s illness.

Nancy Carroll is simply stunning in the central role of Hester and delivers a powerhouse performance. Her depressive angst is writ across her face for the entirety of the play, worn down by a passion that both her and her lover Freddie Page knows is not good for either of them. In lesser hands Hester could have been delivered in a stereotypical melodramatic fashion but instead Carroll produces what feels like a truthful representation of a woman on the brink of suicide, making us feel every ache and emotion she’s going through.

There are many lighter moments in the production too, some delivered by Hester herself, but they never detract from the seriousness of what we’re witnessing. The supporting cast of Denise Black, Ralph Davis and Helena Wilson as Mrs Elton, Philip and Ann respectively were outstanding in their largely comic roles, all three providing light relief without losing sight of the gravity of the Rattigan’s text. Denise Black in particular brought a sense of things teetering on an edge, especially in the play’s panicked opening moments.

The thrust raked stage itself felt it too was teetering at time, balanced upon the bombed bricks and debris of the recently ended war. The sparse set and props were beautifully realised although there were many occasions where we missed the opportunity to see characters’ expressions in key moments, or a view blocked by another actor or piece of furniture. These can be forgiven by the intimacy afforded by performing in the smaller of Chichester’s two theatres which allowed the audience to feel the raw emotion of the central love triangle.

Gerald Kyd brought an unexpected warmth to the role of Sir William Collyer, a man of wealth and power who could easily have slipped into a caricature. Kyd embodies a man who has lost the love of his life, a man who knows that it is a love that will forever remain unrequited no matter how hard he fights. He’s contrasted brilliantly by the younger test pilot Freddie Page for whom Hester has left her husband. Hadley Fraser delivered yet another brilliant performance, at first appearing as caddish and carefree before the realisation that his lack of attention to Hester may have been the reason for the attempt on her life. What both actors superbly highlighted in their performances was the terrible impact a suicide attempt can have on the loved ones left behind – Sir William’s inability of being able to help the one you love alongside Freddie’s descent into self-blame and momentary depression.

Hester’s unlikely saviour comes Matthew Cottle’s Mr Miller. Initially brought in to revive Hester, he makes several reappearances and demonstrates a responsibility to ensure Hester stays alive. A quiet and understated performance, Cottle shows Miller’s own internal toils without ever upstaging Hester.

For ultimately this is a play about one woman living with her own guilt and the ripple effect her actions have on the ones nearest to her. A stand out production that will surely last in the memory and one that highlights very contemporary issues about the causes and ramifications of mental health. Highly recommended.

Nigel Slater’s Toast ★★★★

Performed on 9 April 2019 at The Other Palace, London

Read the original review here

Following a standout run at last year’s Edinburgh Fringe, Nigel Slater’s Toast makes its London debut at The Other Palace. With parma violets, lemon meringue pies and a dash of nostalgia, although the play may not be an entirely slick affair, this can be forgiven for the warmth and energy radiating from the stage.

As you walk into the foyer, the smell of burnt toast lingers in the air, a hint of the sensory treats laid ahead for the audience. Years ago I saw a production of Saturday, Sunday… and Monday and still vividly remember the smell of Italian cuisine wafting through the auditorium. It was reminiscent of this, but sadly the smell of toast stopped at the door on this occasion.

The play itself is based on Nigel Slater’s bestselling memoir Toast about his discovery of the joy of food in his childhood. Told entirely first hand from Nigel’s point of view, Giles Cooper deftly plays the young boy despite being about twenty years older than the character he is portraying. At first I thought it would be jarring to see Cooper playing to a mother who looked younger than him but this was quickly forgotten.

Nigel’s mum was useless at cooking and yet she managed to instill a love of baking (and cooking more generally) that led him to become one of Britain’s best-known food writers. The first act beautifully charts Nigel’s relationship with his mother, performed superbly by the brilliant Lizzie Muncey. Her love for her son spills from the stage and sets a joyous tone for the entire evening, even in some of the darker scenes.

One such moment was Slater’s fractious relationship with his father hitting home when he beats his son in a moment of fury in the corner of the kitchen. Simple but effective, it’s hard to tell if the extra frisson of concern was because I knew I was sat two rows behind the real Nigel witnessing his own abuse.

The set itself was a simple 1960s-styled kitchen with an Aga in the corner, a Smeg-style fridge, and cupboards lining the upstage walls. Countertops would be wheeled to and from centre stage as required, various props appearing and disappearing through various doors. My hopes of the smells of live cooking on stage were quickly dashed when the jam tarts being made in the opening scenes were quickly replaced with ones they’d made earlier, a trick used throughout the show, often to comic effect.

That’s not to say that food isn’t integral to the director’s vision. Following a brilliant choreographed scene involving bags of pick & mix, the cast ventured into the aisles to share with the audience. While this was a nice touch, the subsequent rustling of sweet wrappers left the poignancy of the following scene underwhelming. Similarly during a scene where Nigel and his stepmother Joan battle to produce the best lemon meringue pie to win his dad’s heart, the cast offered up miniature versions to us. As much as I love sweet treats and free food, these moments were an unnecessary gimmick.

Jonnie Riordan’s choreography is fantastically enjoyable. Although these set pieces don’t always quite sit comfortably alongside the rest of his direction, it was very clear that he has a particular style and vision for the production which on the whole works strikingly well.

The five-piece cast are outstanding, with Marie Lawrence and Jake Ferretti each playing multiple roles deserving particular attention and praise. While Cooper fumbles his lines a few times, he carries the show from beginning to end, maturing before our eyes over the evening from nine-year-old boy to a seventeen-year-old young man getting a job in the Christmas kitchen of the Savoy.

Despite a few press night mishaps (including a mixing bowl being unintentionally knocked to the floor during the play’s opening line), Nigel Slater’s Toast is a warm crowd-pleaser of a show, passionately baked and dished up with aplomb.

Closer

Performed by Putney Theatre Company on 19 February 2019 at Putney Arts Theatre in London

Read the original review here

Patrick Marber’s classic play ‘Closer’ is renowned for its brutally honest depiction of the transient nature of love, sex and relationships, and the discretions that fall within these parameters. It is rarely performed outside of a professional setting due to its risqué language and harsh truths so any theatre willing to be brave and stage a production deserves enormous credit for taking such a bold choice. Unfortunately, Putney Theatre Company’s production contained a number of problems that led to an incohesive final product.

The set design and use of projections were strong throughout and high praise must go to Zoe Dobell for her striking designs. Constantly in use and working well to set each scene, a minor technical glitch in the opening scene was quickly forgiven, as were the family of flies who seemed determined to upstage the performers with their shadows. The use of some static furniture may have helped to speed up some of the slower scene changes, but I’m not sure this would have rectified the overall lack of pace in the play.

At a whopping 2 hours and 30 minutes, the play suffered from a distinct lack of energy and drive. The opening scene set the tone for the rest of the evening, with what should have been a flirtatious first meeting between Alice and Dan coming across flat. Even the brief arrival of Larry cameoing in the scene failed to inject any sense of jealousy in Dan or excitement in Alice.

For a play that relies so heavily on the relationships between the four characters, there were very few moments where any of the characters felt like they were connecting with one another. A brief moment between Grace Cullen’s Alice and Olivia Iordache’s Anna in Act 2’s museum scene provided the night’s only believable moment of connection, with an honourable mention going to the strip club scene opening the second half. In fact, I’d go so far as to say that it felt like all four performers were appearing in different versions of the same play.

Jerome Joseph Kennedy’s portrayal as doctor Larry began quite overplayed with unnecessary wide eyes overworking the comedic elements, but by the end of the play he was my favourite of the quartet. He eased into the part as the evening wore on and I came to realise that perhaps his moments of overacting were to compensate the lack of energy elsewhere in the production. Grace Cullen suffered with the same inclination to overact in some scenes but on the whole produced a likeable Alice, with her thoughtful choreography in the act two opener really strong.

Olivia Iordache’s Anna never quite got up to full speed, with many of her scenes jarring against Kennedy’s enthusiastic tendencies versus Tim Duthrane’s lacklustre Dan. In Marber’s script we meet Dan as a bit of a wet fish, an obituary writer whose life is markedly improved by the arrival of Alice, before reverting back to form by the end – none of this would have been obvious from Duthrane’s one note performance, making the audience question what on earth either of the women see in Dan other than his good looks.

The staging and direction from Jeff Graves worked well but unfortunately this doesn’t make up for the fact that none of the performers were really able to bring their characters to life, nor was there any sense that any of the characters wanted to even be in the same room as one another – a massive problem in a play about relationships.

I watched the production on opening night and I really hope the cast begin to gel together and quicken the pace before this run ends – Marber’s script remains as sharp as ever and, having seen Graves’s previous work, I know he is capable of pulling out strong performances from his casts. I had high hopes for this production and I really hope it gets a much needed kick up the backside before the end of the run.

Goats

Performed on 1 December 2017 at Royal Court Jerwood Theatre Downstairs

Read the original review here

“Everything is fine” is a mantra that repeatedly displays on the TV screens flanking the stage in Liwaa Yazji’s ‘Goats’ but unfortunately the same cannot be said of this inconsistent and, at times, incoherent play.

Set in a Syrian village in wartime, ‘Goats’ explores the loss of children not returning home from battle, through the lens of a propagandist government. The play is largely a battle of the lone grieving father Abu Firas pitted against the statesman Abu Al-Tayyib – one constantly questioning the other’s absolute regime. Unconvinced that his son is in the basic wooden coffin laid out before him, Abu Firas sets out to prove that Abu Al-Tayyib’s fight against “terrorists” may not be entirely truthful.

Carlos Chahine as Abu Firas delivers a powerful performance throughout, a man broken by the loss of his son and the uphill struggle to question authority, forced to renounce his claims in order to visit the morgue. Equally Souad Faress as Imm Ghasson gives so much with saying very little, particularly in her largely silent first act.

In fact, it’s probably fair to say that performances throughout were generally very good, save for a couple of the younger actors who were at times a little wooden. Not that it would have mattered as seemingly the audience were more interested in the performance of the live goats on stage. Given to families as compensation (bribe?) for their loss, the goats serve as a visual reminder of the child they have lost. Although I’m pleased to see that the production didn’t shy away from using live animals, nor were they ushered away after a few minutes in the limelight, it seems much of the audience were more interested in the performance of the goats than the humans and their words, coos and laughs out of sync with the play. But maybe that’s the point? Give them a distraction so they won’t think about the facts they’re spoon-fed or, as one character points out, why their sons only ever return dead instead of wounded.

There are some very neat visual flourishes too – the TV screens for example used throughout, at the start as a quick guide to Arabic terms, or as a live news stream for Sirine Saba’s beautifully coiffed Presenter, to a mix of CCTV for the morgue and as night vision for the young men. The Presenter’s news story interrupted by a holding message of fields and clouds and the strapline “Everything is Fine” every time the villagers don’t tow the party line.

Unfortunately, there are quite a few things that aren’t fine. In one confused scene, the four teenagers start to speak of their sons – are they mimicking what their fathers would say about them? Is this a flash to the future? Similarly, it was only when I checked in the programme that I realised Sirine Saba was playing two characters and that the Presenter was not Imm Al-Tayyib, wife of Abu Al-Tayyib. It was also unclear which characters were related to which – I thought it was obvious that Ishia Bennison’s Imm Nabil was wife to Abu Firas but their lack of relation on became clear much later.

‘Goats’ should be a vitally important play. It should force Western society to realise what oppressive regimes are doing in Syria and in similar war-torn countries. Instead the muddled production confuses and bewilders. There are a few laughs (a mobile phone ringing out at an embarrassing moment being a personal highlight) but ultimately the message is unclear, saved only slightly by a relatively slick production.

Manwatching

Performed on 16 May 2017 at the Jerwood Theatre Upstairs, Royal Court in London

Read the original review here

Written by an anonymous woman to be performed by an unrehearsed man, Manwatching is a personal and honest account of female sexuality, relationships, masturbation, and more. As a male reviewer it’s hard for me to confirm just how honest the writing is but, judging by the laughter and applause from the women in the room, it’s a safe bet to say it’s pretty accurate. Although that’s not to say that I didn’t find it funny too (I did) or that I couldn’t relate to stories being told (I could).

It’s an interesting play to review as the premise relies on the performer not having read the text in advance. Similarly, the reviewer doesn’t want to spoil the content of the performance for a future audience member as much of it hinges on surprise and spending the hour wondering what will happen next.

The Jerwood Theatre Upstairs at the Royal Court is a brilliant venue I’ve visited numerous times but, in this setting, stripped back down to a bare and basic black room, one realises just how intimate the space is. Entering the room I was immediately confronted by nearly 100 people who had already taken their seats, a slightly unnerving experience and one that I then participated in once I took my seat. On the stage were two podiums – one with a printer, the other with a jug of water, glass and a Double Decker.

The eleven night run at the Royal Court has an array of male stand-up comedians performing the unseen text, reading it aloud for the first time in front of strangers unaware of who will be in their cast. There is a line in the play about how society privileges the male voice and I couldn’t help but wonder if I believed what I was hearing because it was being told to me by Rob Beckett (of whom I was already a fan). I’d like to think I’d have found the jokes funny and the stories true if it were being read by a woman, but I guess I’ll never know.

The writer discusses her past relationships with men, what she finds attractive, how she would rate her own looks, her fantasies and failures. There are other things I’d like to mention but to do so would take away the impact that the reveal of some stories have. The anonymity is key and is used to liberate her from the fear of being judged, trolled or ignored. Rob Beckett, despite adlibbing at the start he’d not read anything this long in public for years, performed the text well, if a little fast, almost as if he wanted it over with quickly.

However, as much as I laughed and enjoyed the anecdotes I was being told, it didn’t leave me with any particularly strong feelings about what I’d seen. There was no rush to rave about it on social media, no desire to dive straight into the text I’d just bought (their play scripts are a bargain at £3). It was an interesting if throwaway show, worth seeing once, although as I write this it dawns on me that it strikes a similarity with watching a stand-up routine – you enjoy the experience at the time but it doesn’t necessarily leave anything lasting within you.

CTRL+ALT+DEL

Performed on 9 August 2016 at Camden People’s Theatre in London

Read the original review here

As part of the Camden Fringe Festival, writer and performer Emma Packer has brought her one woman show back to life following a run at Edinburgh in 2014. Described by Amnesty International as a powerful production worthy of being seen as both a theatrical and activist piece, CTRL+ALT+DELETE is the story of Amy Jones, a young girl close to her grandfather but essentially unwanted and abused by her mother.

Let’s get the title out of the way first – if you’re expecting to see a piece integrating and making use of technology in some way then you’ll be disappointed. In fact there’s no relation, from what I could tell, between the title and the subject matter or overall production.

Without question, Packer can write. She’s a very good writer in fact with some very good one liners and eloquent moments of prose. However this didn’t sit comfortably with the Brixton teenager she spent most of the play portraying. Of course there are bright, intelligent young people living in the most deprived areas of the UK and I’m not suggesting that they’re incapable of having bright minds. But almost immediately Amy was represented as a girl unrealistically wise beyond her years and therefore some of the language used just didn’t feel right coming from her mouth.

On the flip side, Amy’s monstrous mother, also played by Packer, was a fantastic creation – almost perfect in fact. She completely nailed the accent, delivery and tone and, despite how repulsive she and her behaviour were, the mother was the character I looked forward to revisiting the most. The section on what is considered acceptable language was a particular highlight, from birthday cards containing the c-word to describing people with learning difficulties and disabilities, it was genuinely very funny and raised interesting points.

I had two big problems though with the overall piece. Firstly, have you seen that episode of the sitcom Friends where Chandler is abandoned at a one woman show and forced to awkwardly listen to the actor describing her first period? Unfortunately CTRL+ALT+DELETE fell into the similar trap when Amy literally described being in her mother’s womb. It was a frankly embarrassing moment to witness with no bearing or consequence on the rest of the play.

My biggest issue was with the amount of political activism crammed into the hour. From David Cameron to the Tottenham riots with a bit of Brexit mixed in for this revised production, the second half in particular was relentless in pushing forward its message, at times coming across as a lecture more than a character study.

It’s obvious that Emma Packer is a very strong character actress, a point confirmed after having seen some of her videos on YouTube, and I’d be interested to see a show with a whole mix of her character creations. I’m not against theatre that challenges issues in society and our political hierarchy but CTRL+ALT+DELETE didn’t hit the mark.

Waiting for Godot

Performed by Guildburys Theatre Company on 8 April 2016 at The Electric Theatre in Guildford

Read the original review here

Waiting for Godot was most famously reviewed by Vivian Mercier as a play where nothing happens, twice, and after seeing the Guildburys Theatre Company production I’d agree entirely. But that is not to say that it wasn’t an enjoyable evening of theatre.

The play focuses on two companions waiting by a tree for the eponymous and elusive Godot. Vladimir (or Didi) comes across as slightly more mature, taking charge of the situation they are in. He is played here by Dave Ufton who, despite an early prompt, never faltered in his characterisation. I feel it would be unfair to talk about him in solace as this is a play that relies heavily on the partnership with Tim Brown’s Estragon (or Gogo) who mostly obediently follows his friend’s instructions to wait until nightfall for Godot before taking shelter and returning the next morning. Brown’s Irish accent leant Gogo a slightly more playful tone, living much more in the moment than the slightly angst-ridden Didi. Ufton and Brown were a brilliant double act, particularly in their moments of slapstick but also during more sombre moments.

They are joined in their moratorium by Pozzo (Phill Griffith) and his slave Lucky (Tom Kent), tied to a rope and kept at a distance from his master. Griffith brought a manic urgency to the (lack of) proceedings, commanding the barren wasteland like a steampunk circus ringmaster and having Gogo and Didi engrossed in his tales. The mute Lucky stared out into the wilderness with dead eyes for much of the first act and I was questioning how I would judge Kent’s slightly awkwardly stood oddity of a character. This was until he launched into a long, punctuation-less monologue that seemed to go on forever but one that built in passion and ferocity and ended with the audience’s round of applause. Kent has a truly beautiful speaking voice, no doubt made more appealing following the incredibly long silence that preceded it. Contrasted with Griffith’s more egomaniacal presence, this was another pair that worked very well together. The final member of the cast, Jordan Gunner as Godot’s messenger boy, well-spoken and more youthful than the rest. A fine young actor who, based on his two brief appearances, will no doubt go on to more prominent roles in the future.

I was a big fan of all the production elements, the costumes by Jemma Jessup, Derby Phillips and Clive Rubero in particular, especially Gogo’s dirtied yellow hoodie which brought the production into the modern age and a slight sense of apocalypse, although I think Didi’s overcoat and Gogo’s hat could have been much tattier. Ian Nichols’s set design was equally brilliant – simple yet with enough detail to make the place believable. A big round of applause must go to director Oli Bruce who created an outstanding production full of rich performances and a clear understanding of proceedings. My only gripe would be that I felt the four main actors were perhaps twenty years too young – I’ve not read the play but from how the text was performed there was a sense that some pairings had been together for half a century.

In all honesty, I kept willing for the play to actually do something. A lot of the time it felt slow but to be clear I don’t think for a moment that this was a pacing issue from the company – in some ways I think that this was Beckett’s intention, a sort of test of endurance for the audience. But this particular production in the hands of Oli Bruce was absolutely excellent and a real triumph – I can’t wait to see what he does next… (I’ll get my own coat)

Educating Rita

Performed on 23 June 2015 at Chichester Festival Theatre

Read the original review here

A new Chichester Festival Theatre production tends to be something to treasure, with some shows taking a successful leap to the West End. Sadly, I don’t think the same can be said of Willy Russell’s hilarious Educating Rita.

Press Night is possibly the worst occasion for an actor to dry up and unfortunately this happened to newly knighted Lenny Henry. Forgetting one’s lines happens to most actors at one point or another, be it amateur or professional. But this is the first time I’ve seen an actor break character, apologise to the audience and then leave the stage to compose themselves. This could be forgiven if Henry then returned to give a powerhouse performance; this was not the case.

For those unfamiliar with the story, Frank (Lenny Henry) is a university professor with an affection for drink, stashing bottles of booze behind the literary greats lining his large office. He agrees to take on an Open University student named Susan (Lashana Lynch), a Liverpudlian who chooses to use the name of her favourite author, Rita Mae Brown. She wants culture in her life, something that her job as a hairdresser and marriage to a man expecting the delivery of a family just isn’t providing her. Frank is taken aback by Rita’s carefree attitude, a breath of fresh air amongst the dusty bookshelves.

When thinking of the play I can’t help but think of Julie Walters in the title role – a standout cinematic performance following the role she originated on stage. But Lynch is definitely a worthy contender. Sure, her accent wasn’t faultless but she utterly inhabited her character, with every word, look and step delivered with measured precision. She may be in the early stages of her career but she’s definitely one to look out for.

The same certainly cannot be said of Henry. I can forgive drying up and forgetting lines – hell, I’ll go the whole hog and let him off leaving the stage. But I just didn’t believe what he was saying. Frank has an air of arrogance and bottled anger about him that Henry just plainly didn’t portray convincingly, showing very little confidence in what he was saying. The worst moment was when he angrily turns on Rita – the words were there but I heard nothing in his voice that made me think or feel that he was serious. Perhaps his shortfalls were magnified by the brilliance of Lynch although I’m not convinced by that argument.

Karen Large’s costumes were fantastic, bringing the 80s right to the fore through Rita. The change of jackets and cardigans for Henry between scenes also helped with the passing of time. The set was a gorgeous creation – floor to ceiling bookshelves and occasional piles of books littering the floor. From where I was seated it appeared as if Henry disappeared into the bookcase behind him, a clever trick to assist in a quick change. A shame then that the same trickery wasn’t employed in the scene change to the final scene – a lengthy wait as stage hands removed books to put into boxes. Empty shelves and full boxes were important to the plot but Ellen Cairns’s design surely could have found a more creative way around this.

Michael Buffong’s direction also left a lot to be desired. He’s certainly assisted the talented Lynch in making Rita her own – her year-long transformation beautifully created before our eyes – but there were many blocking issues. Chichester’s Minerva Theatre is a tricky space to work with and Buffong needed to ensure the entire audience were being catered for rather than the lengthy periods of watching Henry blocking our view of Lynch on my side of the auditorium. During a Q&A earlier the night before Press Night, Buffong apparently admitted that there were still blocking issues to iron out. Perhaps this is where the heart of the problem lays – an under-rehearsed leading man in a play beset with incomplete staging.

Alongside Lynch’s performance, the other saviour for the evening was Russell’s hilariously witty script, one that has stood the test of time very well. Frank and Rita’s mostly platonic relationship is wonderful to watch and listen to, no matter how bad Henry’s performance was. Surprisingly, about a third of the audience felt the need to give the production a standing ovation but I can’t help but question if this was out of pity for Henry’s earlier shortfall or out of some kind of nostalgia to the thirty-plus year old text.

A great play featuring a stellar performance from Lynch, but let down by Henry and some poor direction in places.

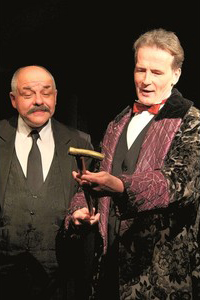

The Hound of the Baskervilles

Performed by Dorking Dramatic and Operatic Society on 21 October 2014 at The Green Room Theatre in Dorking

Read the original review here

The cases of Sherlock Holmes have been thrilling audiences of literature, and their stage and screen adaptations, for over 125 years. Arguably one of the most popular and well-known of these tales is Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Hound of the Baskervilles, given a new lease of life in Bob Hamilton’s adaptation for Dorking Dramatic and Operatic Society.

Set predominately on the brooding hillsides of Dartmoor, the play tells the story of a legendary supernatural hound that has haunted the Baskerville family for generations and is believed to be the cause of death for Sir Charles Baskerville. The case is brought to the attention of Holmes and Watson by Dr Mortimer who fears for the life of Sir Henry Baskerville, the only known heir to Baskerville Hall.

It was quickly apparent that this adaptation was a labour of love for Bob Hamilton, who notes in the programme that he first read the book as a teenager. As Dr John Watson, it was Hamilton that was the primary focus for the play and he brought a wealth of subtlety, humour and presence to the role – a truly excellent performance through and through. Don Brown as Sherlock Holmes gave a solid performance – his height on stage certainly assisted when it came to him to take charge of situations of peril. There were a few stumbles over words during his notorious deductions, something that I hope can be ascribed to opening night nerves – but this shouldn’t detract from a strong interpretation of the character.

Michael J Leopold as Sir Henry Baskerville brought the right balance of fear and resolve to the young heir, returning to England from Canada to seek his inheritance with a very convincing accent. As Sir Henry’s ally Dr Mortimer, Michael May gave a spritely performance. In fact the cast overall delivered some great performances, especially when it came to supporting cast providing ensemble roles. I particularly enjoyed the versatile performance of Linda McMahon who delivered three individually distinctive characters, especially as Mrs Mortimer channelling the spirit of Sir Charles Baskerville. McMahon commanded the stage in this séance scene assisted brilliantly by the breathing soundscape delivered by the rest of the cast. Brian Inns as Giles Franklin injected Act Two with energy following his short-lived appearance at the start as Sir Charles. Sophie Toyer deserves special mention too for her striking performance as Beryl Stapleton. Rounding out the cast, Terence Mayne as Mr Barrymore, Olly Reeves as Jack Stapleton and Victoria Brooks as Laura Lyons all delivered fine performances.

Director Sandra Grant showed promising signs of creativity with this production, very ably assisted by the talented technical direction of Stuart Yeatman. A particular highlight was the cast holding picture frames as if paintings of the Baskerville dynasty in the great hall, almost evoking the magical portraits of the Harry Potter franchise. There was a simple beauty in the ensemble holding black sticks with fluttering butterflies surrounding Jack Stapleton. Movement Director Tracy Bargate worked wonders with the cast on some very strong visual moments, with a rocking train carriage and Sir Charles running for his life particularly memorable.

The set was starkly simple – a silhouette of the moors covering the entire upstage provided a constant reminder of their bleak existence, with only white gauze behind it. This was particularly effective in certain lights when the stage filled with fog. The gauze was used to great effect on many occasions – the projection of a full moon shining brightly over the stage, the occasional glimpse of text being read as part of Holmes’s deductions. We were treated very early on to shadow puppetry to recall the legend of the hound but unfortunately this was to be their only appearance, a missed opportunity to use the device considering the scale of the moors dominating the stage. Similarly, we only had two very short appearances of the eponymous Hound, a fantastically designed puppet operated by Edd Mott with members of the cast. I am not suggesting that we needed to see more of the hound but it did feel a shame not to have had more time with it.

The second act felt a little too long, with some scenes repeating previously heard information. However, Hamilton’s work as a writer should not be underestimated as he has delivered a very fine adaptation of this classic story. With some wonderful performances, the Hound of the Baskervilles is a visual delight and very much worth catching before the run ends on 25th October.

The Musicians of Silence

Performed by Mummenschanz on 25 July 2014 at Peacock Theatre in London

Read the original review here

The Musicians of Silence by Mummenschanz is a bit of an oddity for me to review – a show where we never meet the performers, nor do we hear their voices or any sound other than the ones they create. A visually stunning and technically complex production but, unfortunately, one that left me feeling a little empty by the end.

From the start it is obvious that Mummenschanz are experts in their field – with over forty years of experience and, as the programme states, “a company older than perhaps a large percentage of its audience”, the troupe has had runs on Broadway and appeared as guest stars on the Muppet Show. The show opens with a giant hand peeling back the curtain, waving to the audience, giving us a thumbs up, and performing other typical ‘hand’ gestures, albeit with legs in black tights protruding from the wrist. After waving us goodbye a second hand appeared in the aisle, moving amongst the audience to stroke their hair, make lunges at audience members and to pat their heads. The white gloved hands against the red curtain was visually striking and proved memorable as the evening wore on. Unfortunately, the visual gag of the hands twiddling their thumbs became a bit of a prophecy for later in the show.

The evening could be most likened to a comedy sketch show that had been made over by Pixar Animation Studios. Many set pieces reminded me of Pixar’s early work of humanising inanimate objects, most notably when Mummenschanz had a giant slinky-style tube and balloon I couldn’t help but think of Pixar’s lamp playing with a ball. Similarly, with other fantastic costumes such as the giant green pea with a tongue, it felt at times like we were watching a live action cartoon. Not necessarily a bad thing.

I was less impressed when the performers donned masks. Their faces still obscured, we were treated to masks made from toilet rolls to giant malleable pipe cleaners to clay, the latter in particular being most skilful with the two clowns adding additional bits of clay to adapt their masks – even more impressive given that they were working with no mirrors yet able to create very distinct shapes and creatures. However, I found all of the sections with masks long and a little self-indulgent, particularly when one performer entered the audience wearing a cube on her head and encouraging the audience to add tape to it to create faces and shapes. It worked as scene-change filler but, like most of the evening, the turn went on for a little too long and felt rather pointless, such as the ‘lovers’ wearing toilet roll masks – a good visual gag but one I wanted to end in half the time they took. There were however some beautifully stunning moments. A school of glow in the dark fishes being chased by a larger fish was particularly clever, or the giant floating sheet of paper that contorted itself into various faces.

The most disappointing thing was when the larger set pieces failed due to a lack of synchronicity between the performers. This was most evident with two giant eyes, nose and mouth used to create a face. At times the eyes would blink but were a split second out of time with one another, bringing the illusion crashing down. It was a real shame and could easily have been solved with the addition of some kind of music or rhythm. The lack of music in the show made the evening feel longer than it was – at under eighty minutes, this isn’t really something that should have crossed my mind.

But perhaps I’m becoming too cynical. There were a lot of children in the audience who clearly delighted in seeing the visual treats on stage and occasionally stepping off to venture out into the auditorium. Looking on Twitter after the show it was evident that many parents reported how much their children loved it and reminded me how important it is for them to witness such skilful and powerfully visual theatre from a young age. For me, however, many of the sketches were too long and some of the performers’ timings were also out, a surprise given the number of years the company has been performing. It was a clever and skilful show but one that needed trimming in a lot of areas.

Under Milk Wood

Performed by Clwyd Theatr Cymru on 16 June 2014 at Ashcroft Theatre at Fairfield Halls in Croydon

Read the original review here

It is hard to know where to start a review when a production such as Clwyd Theatr Cymru’s version of Dylan Thomas’s classic Under Milk Wood is as good as the evening I spent at Fairfield Halls in Croydon. So let us begin at the beginning…

Opening at night in the town of Llareggub, the narrator introduces us to a multitude of characters through their dreams, torments and mid-sleep ramblings. We could have heard a pin drop as Owen Teale opened the show as First Voice, his deep Welsh accent echoing through the auditorium. My experience of Teale has been through the antagonists he has portrayed on television in programmes such as Game of Thrones and Torchwood, so it was at first unsettling to witness his warm-hearted and caring performance on the stage in front of me. My memories were quickly overshadowed by the comforting power of his delivery of Thomas’s beautifully lyrical text. First Voice was a constant presence in the production, ably supported by Christian Patterson as Second Voice and Ifan Huw Dafydd as Captain Cat, unafraid to take a backseat at times to allow the ensemble to step forward in and out of the various inhabitants of Llareggub.

And what an ensemble we were treated to, with every actor moving deftly between each of their characters. Sophie Melville was a particular treat, shifting from doting wife Cherry Owen to brittle Mrs Pugh and others in between, giving each one their own clear identity. Similarly Caryl Morgan as Myfanwy Price daydreaming of marrying her love or as the seventeen year old “never been kissed” Mae Rose Cottage, and Hedydd Dylan as single mother Polly Garter singing hauntingly for her lost loves or portraying the ever nagging Mrs Ogmore-Pritchard refusing to take guests at her bed and breakfast.

At the mature end of the female cast was the wonderful Sara Harris-Davies as the horrified Mrs Butcher Beynon tricked into eating dogs’ eyes and owl’s meat, or as Mrs Willy Nilly steaming open her postman husband’s letters before he makes his daily rounds. It is fair to say that many of the female characters were wives to male characters as opposed to flying solo – far from being a criticism, a majority of the women were central to evoking the sense of the place, the hustle and bustle of the small Welsh fishing town, and we were left in no doubt that the women were independent and strong-willed.

Like the female half of the cast, the four male ensemble actors were each fantastic in their own right too. Simon Nehan switched from the brutish Butcher Beynon to the mild-mannered Rev Eli Jenkins with such an ease that I was convinced they were played by different actors. I felt Kai Owen was a little underused, his Cherry Owen in particular at times proving he could have been handed an additional memorable character. However, he really came into his own with a drunken singsong near the end of the show, his beautiful singing overshadowing the rowdiness of the ensemble.

There were, however, two members of the ensemble who battled it out to steal the show. Richard Elfyn was excellent as Mr Pugh dreaming of poisoning his wife and as the enamoured Mog Edwards, betrothed in his dreams to Myfanwy Price – a standout character actor that I feel honoured to have seen perform. His opposition was the equally superb Steven Meo who I found myself always wanting to see more of. From the overly camp gossiping postman Willy Nilly to the child Nogood Boyo through to the publican Sinbad Sailors, Meo never failed to raise a laugh in the audience – and, on a couple of occasions, amongst the cast too. After two months of a relentless tour, it is heart-warming to see the cast still taking joyous pleasure in one another’s performances.

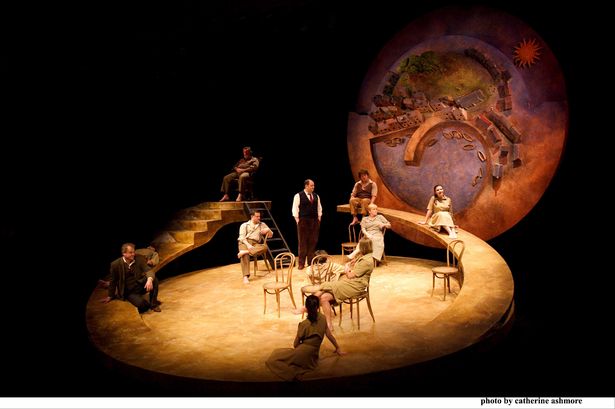

Martyn Bainbridge’s design work was inspired. The circular stage, with its edges unpeeling as they approached the rear, was echoed on the upstage wall by a bird’s eye view of the circular town, with fishing boats and causeways and little houses with even littler windows that lit up. The two sections reminded me of an opened pocket-watch, a clever yet subtle suggestion to the twenty fours we spend in Llareggub.

Overall, it was Owen Teale’s predominant storyteller that provided the production a cohesiveness that other productions might have struggled to portray. This year marks one hundred years since Dylan Thomas’s birth and is also fortuitously the 60th anniversary of the play’s British premiere. Many years in the making, Dylan Thomas never got to see the great Richard Burton lead the very first production, having died at the age of 39 just two months earlier. This production is a truly fitting celebration of Thomas and his final dramatic work, one that the cast and creative team should be incredibly proud of.

Under Milk Wood is at the Fairfield Halls in Croydon until 21 June, before continuing the tour until 12 July. I would highly recommend catching it whilst you still can.

The Birds

Performed by Putney Theatre Company on 5 September 2013 at Putney Arts Theatre in London

Read the original review here

As a big Hitchcock fan, I jumped at the opportunity to review Conor McPherson’s ‘The Birds’, which had its UK premiere this week. This play, and Hitchcock’s masterpiece, are both inspired by the Daphne du Maurier short story of the same name but both veer off in different directions. The original story focuses solely on farmer Nat and his struggle to keep his family safe from flocks of birds attacking their home, eventually barricading themselves in the farmhouse kitchen. A confined tale, the story is around 15 pages long and, as McPherson told me in a recent interview with him, one that ends abruptly as if it were the first chapter of a much longer book. McPherson picks up the narrative a few weeks later and this is where we join the play.

There are very few similarities between McPherson’s Nat and his namesake in du Maurier’s original story. We open with Nat shivering under a sleeping bag, a high fever causing nightmares about his ex-wife. Gone is the reluctant hero of the original, replaced with a man living on the edge in a dangerous new world. There is an early glimmer of insanity when Nat reveals to have previously been institutionalised by his ex, insisting that she was in fact the mad one. McPherson often allows audiences to fill in the gaps in his plays but this particular thread was left dangling and was barely referenced again, a shame in this instance as Barney Hart Dyke’s performance was certainly capable of developing this further. Hart Dyke portrayed Nat sensitively throughout the play and was thoroughly believable as a man caught between two women vying for his attentions.

One of these women was Diane, a successful writer estranged from her husband and daughter, who we first meet helping Nat to recuperate from his illness. Much of the story is narrated by Diane’s voiceover as she scribbles away in her notebook, her private thoughts and platonic love for Nat developing as the story progresses. Penny Weatherall was excellent as Diane, driving the story forward as an almost matriarchal figure. In writing ‘The Birds’, McPherson was keen to tell the story from a woman’s perspective and shifting focus from Nat to Diane was a masterstroke, particularly with Weatherall’s beautifully measured performance. Her fear at the sudden and unexpected arrival of neighbour Tierney, a loner who had clearly been observing the house for some time, was mesmerising to watch. The short scene with Weatherall and Michael Rossi as Tierney was excellent, the latter striking an imposing figure in such an intimate setting, and provided the impetus for Diane to question the motivations of Julia.

A younger woman travelling with what sounded like a bunch of violent scavengers, Julia claimed to be seeking refuge from her former bedfellows but appeared to have ulterior motives and set her sights on older man Nat, her behaviour at odds with the bible reading persona she wanted to project. Emily Sarah Howarth delivered a believable performance but at times I felt she could have pushed herself a little further, particularly during her showdown with Diane or when flirting with Nat; she had a devilish ‘come to bed’ look in her eyes when it was required but could have provided a little extra sparkle at other times.

Director Jeff Graves has clearly worked hard with his actors with very worthwhile results creating all round very good performances. Tony Bennett and Gabriella Ihasz’s set design was impressive – wooden panels and a brown sofa instantly evoking a sense of Small Town America – brought to candlelit life by Antony Vine’s lighting design, as well as the actors’ solid American accents. I was particularly keen on the shuttered windows that opened to reveal cracks of light appearing through boards to protect the glass from the oncoming threat. However, the whole production remained consistently clean from beginning to end – I wanted to see Diane’s pristine white t-shirt get gradually grubbier, or Julia’s Tippi Hedren 60s-inspired beehive hair to become messy and wild as the days and weeks went on, but instead not a single hair came out of place. Similarly, I thought the set dressing needed to develop to suit the changing timescale of the play; when characters were talking about a shortage of food I could still see the same half a dozen tins on the shelf behind them that had been there since scene one. A dirtier and scarcer set would have enhanced the almost apocalyptic tone even further.

Before attending the performance, I was fearful that we would be subjected to seeing fake birds attempting to scare the audience, a notion that is laughable in its conceit. McDonagh informed me that the original Irish production used live trained birds at the climax – which worked well until Press Night when some flew into the audience and rafters whilst others sat stubbornly in their starting places. Following workshops with the play in Minneapolis, the author very wisely removed this element from the final published version and instead relies on the sound of the titular birds to provide the menace. Ian Ward sourced some very believable effects for his sound design and on the whole they worked well, although I would suggest Ward should not be too afraid of amplifying them and almost bombarding the audience into feeling the same claustrophobia as the characters in the play.

‘The Birds’ was a very enjoyable production overall, a play that lends itself excellently to Putney Arts Theatre’s intimate Studio Theatre. A few small changes here and there, although subtle, may have paid huge dividends, but this shouldn’t detract from what was a very good night of theatre.

Henry V

Performed by Network Theatre Company on 21 June 2012 at Network Theatre in London

Read the original review here

I’m not the biggest fan of Shakespeare. There. I’ve said it. Don’t get me wrong, I completely appreciate why the Bard is held in such high esteem and how his plays have outlived the man himself by hundreds of years. But my personal preference would be a more contemporary play, a reflection of modern living. So I was more than pleasantly surprised at just how much I enjoyed Network Theatre’s version of ‘Henry V’.

It may be theatrical social suicide to admit that my knowledge of the plots and characters of Shakespeare is quite scarce, but on the plus side I find that it allows me to watch a production with an open mind. For my fellow dunces, the play follows King Henry leading the English troops into the Battle of Agincourt to fight the French, and the subsequent wooing of Princess Katherine. On hand to guide the audience throughout is Chorus, a character written partly to paint images of battlefields in our minds without requiring huge set pieces but to also tell us where in the story we are. James Killeen as Chorus was superb, a performance that at times was brilliantly hilarious and at others quietly moving. In particular, the scene in which he finds himself suddenly thrust from narrator to the frontline was an inspired idea and very funny indeed.

In the title role, Stephen Lee was equally a joy to watch – from rousing the troops with his stirring speeches, to anger at betrayal from his Earls, to the comical wooing of Katherine: Lee’s grand performance ensured the play maintained a sense of majesty. Despite a slight stumble over one of his early lines, Lee proved to be a very excellent actor.

In fact, a majority of the company’s performances were of a very high standard, with Andrew Cleaver as the Dauphin and Simon Dobson as Sgt Pistol particularly springing to mind. The biggest laughs, however, were reserved for Delphine Gauchin (Katherine) and Emily Godowski (Alice) in a short but memorable scene where the Princess is taught the English translations for various body parts.

Network Theatre itself is pretty much a standard black box but the use of just a few key set pieces allowed for a minimalist approach to an epic battle – proof that all you need is good lighting, convincing actors and strong direction. Julian Farrance is clearly a very talented director. Other than one or two less convincing performances, the cast were strong throughout from lead roles to minor unspeaking background parts – this is no mean feat when there are 25 actors playing listed characters and additional company members in other roles. Farrance’s decision to bring the play forward 400 years to the Napoleonic War was a very good move which allowed for some beautiful period costumes from director Farrance and producer Sacha Walker. The sound design was excellent, as was Emma Byrne’s lighting design.

An excellent production. I’d like to thank Sardines for giving me the opportunity to review this play as without it I wouldn’t have discovered this little gem of a theatre. Based on the strength of Henry V, I would thoroughly recommend a trip under Waterloo station to see Network Theatre’s future productions – I certainly intend to visit again in the future.

Dracula

Performed by Dorking Dramatic and Operatic Society on 27 October 2011 at The Green Room Theatre in Dorking

Read the original review here

The premiere of a new play is an exciting time for any playwright and some might think that there is an added pressure when adapting an established work. Dracula, performed for the first time by Dorking Dramatic and Operatic Society, was halfway through its debut week and has had the opportunity to shake off the opening night nerves. It was an enjoyable production with many strong elements to its credit but fell short in a few areas.

As the lights came up we were greeted by three chanting blood-drenched girls drawn to a period chandelier at the front of the auditorium. The darkly lit scene was an incredibly powerful opening image sadly spoiled somewhat by the excitable audience; what should have been a haunting chorus descended into silly giggles. This was not the performers’ fault – Victoria Brooks, Sarah Robinson and Saskia Wilkinson as the Children of the Night stayed true to their characters and provided a menacing presence throughout the play.

Our attention quickly turned to Renfield, played by Martin Tidy, a young man invited to Transylvania by the eponymous Count. A short clever sequence in a solo spot represented Renfield’s journey abroad and very quick descent into madness, before throwing the audience straight into the English mental institute to which Renfield was assigned. Tidy’s performance was captivating for every single appearance he made and an absolute joy to watch. Crispian Shepley, playing Dr Seward, gave an assured performance which occasionally struggled to keep up with Renfield. It was a wise decision to turn Seward into a grieving father but I would have liked a more believable portrayal of his loss. A nervous portrayal of Hennessey by Nigel Ames diluted some of the trio’s scenes together but succeeded in keeping the story interesting.

Bob Hamilton, appearing as Abraham Van Helsing in his own adaptation, dominated his scenes – a brash character with an understanding of the supernatural deaths in the busy shipping town. Hamilton’s performance illuminated much of the play but I felt some of his repetitive explanations of the ongoing phenomena unnecessary. That being said, Hamilton’s writing is very strong and with a few tweaks to the script, Dracula could quite easily prove to be a hit elsewhere.